by Bryan Whitledge

But when one looks at the facts of my life and when I crossed paths with President Boyd, a glaring gap is visible… when Bill Boyd left CMU to become president at the University of Oregon, I wasn’t yet born. In fact, I wasn’t yet out of elementary school when he retired from working life altogether. Even more, it wasn’t until I was 29 years old and President Boyd was nearly 90 years old and had been away from Central for 35 years that I first heard of him. And to cap it off, I never met the man and only on two occasions where I was in the room when he was on a telephone call with others did I get the chance to talk to him, asking him a brief matter-of-fact question each time to which he replied in a similar fashion… in total, we talked to each other for maybe 30 seconds in our lives. None of this is indicative of a personal relationship.

So why is it, with so much time between his tenure and my work at CMU, and having never met President Boyd and only very briefly talking to him, do I feel such a personal connection with this man? The simple answer is because of the power of archives.

I am not the first person, nor will I be the last, to feel this. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin has talked about the intimate relationships she has formed with FDR, Abe Lincoln, and other US presidents, even though she never met them. French researcher Arlette Farge wrote a classic of archives literature in 1989, Le Goût de l’archive (The Allure of the Archives), in which she discusses how “she was seduced by the sensuality of old manuscripts and by the revelatory power of voices otherwise lost.” And it is common for budding archivists, while in graduate school, to get a little piece of advice from one of the veterans working with them when the graduate student gets their first assignment processing and arranging a collection: “Hopefully, you like Ms. X, because you are going to be spending a lot of time with her.”

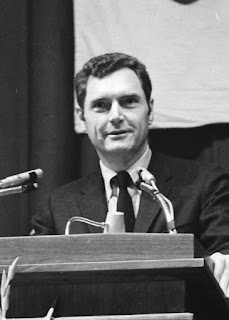

|

| President Boyd and Eunice Kennedy Shriver, 1974 Michigan Special Olympics State Summer Games |

In my case, I first “met” President Boyd in 2011, when I joined the Clarke’s team and began researching the history of the university. I was new to CMU and I didn’t know a thing about the history of the university. So, I was advised to start with John Cumming’s book. I still remember reaching the last 50 pages of the book or so and reading about President Boyd. I was immediately intrigued by him. He seemed like a history-making figure and a decent person. I then dug into the Central Michigan Life student newspaper and the Centralight alumni magazine. When documenting events of the late 1960s to mid-1970s, President Boyd seemed to be at the center of all of the action – anti-Vietnam-War activism, the formation of the Faculty Association (one of the first collective bargaining units for faculty at a 4-year university in the country), CMU moving up to NCAA Division I in athletics, the liberalization of residence hall regulations that forced women students to observe an earlier curfew then men students, and more. And in each case, his actions always seemed wise and he often had something intelligent and reasonable to say.

With that research project, I also dug into the archives of previous university presidents—Anspach, Warriner, Able, and of course, Boyd. The folders of speeches, correspondence, and working files gave me an idea of how each of these people approached their job and what they valued. Working with the Boyd records, I began to really like the guy. By January of 2012, when I had wrapped up the research, I was impressed with President Boyd and thought he was a special person.

As time moved on, I learned more and more about him. In late 2012, I mentioned to a colleague in the History Department about President Boyd’s efforts to increase diversity at CMU by hiring Dr. Robert Thornton, a physicist from San Francisco State University, in June 1969. Dr. Thornton was brought on as a special assistant charged with increasing recruitment of Black students and faculty and providing guidance to incorporate Black Studies into CMU’s curriculum. My colleague said, “Do you realize that San Francisco State was the first school in the country with a Black Studies program and it started in March of 1969?” I had no idea! Just four months after SFSU started their program, Boyd was drawing on their experience to try to improve CMU. One more fact about President Boyd’s sense of decency and humanity was added to my knowledge of him.

|

| President Bill Boyd and Professor Jean Mayhew, "King and Queen of Gentle Friday," 1970 |

A couple years later, I was invited to listen to an oral history interview between Frank Boles, the director of the Clarke, and President Boyd. Over speakerphone, I listened to President Boyd say that he was most proud of making the Central campus more beautiful, and remark on the May 1970 unrest by saying, “I was surprised and pleased by the good nature of the Central student body.” After a couple years of digging into the archives and answering questions about the history of CMU, it wasn’t a stretch for me to imagine being there as he was making tough decisions during a stressful situation.

Two years after that, I spoke to a group of about fifteen alumni involved in the anti-Vietnam-War movement, and I listened as every single person had something complimentary to say about President Boyd. One of the members of the group contacted him via telephone and the conversation that ensued between the alumni and their former president were, to say the least, very touching. After the alumni expressed their gratitude for his leadership and the lessons they learned from his example some 45 years after those moments in history, President Boyd ended the phone call by saying that speaking with all of these former students that day was among one of the best moments of his life. By this point, I felt like I knew Central’s seventh president.

|

| President Bill Boyd speaks to students outside "Freedom Hall," May 1970 |

Over the years, I had many more of these moments in which I learned more about the decency and humanity of President Boyd: when I learned about the change to residency requirements for tuition purposes for the children of migrant workers (pages 6-10 of linked article); when I learned about his plans for his inauguration, which featured a rather subdued ceremony, cancelling classes for the afternoon, and hosting free concert for students featuring activist and folk singer Buffy Sainte-Marie; when I learned about Earth Week. I felt proud to “know” the man behind these stories.

After President Boyd’s passing, I read many remembrances including two from Racine, Wisconsin, where he lived for nearly the last 40 years. Both remembrances (Journal Times and Wright in Racine) mentioned a great many things that I never knew about President Boyd—which makes perfect sense objectively because I really only have access to records from the seven years when he was president at Central. But I wasn’t surprised by these wonderful anecdotes because I “know” President Boyd and the stories match exactly the man I know. The same is true for all of the comments on the CMU Alumni Association Facebook page responding to the post announcing President Boyd’s death. In fact, I felt a sense of pride that all of these people respected and admired him—a man who is part of the Central Michigan University family.

The only things that connect me to Bill Boyd are the historical documents in the Clarke and the stories from people who knew him. But, like Arlette Farge and others can attest, those pieces of paper and statements, as seemingly mundane and innocuous as some might believe them to be, hold a great deal of power—enough power to form a relationship. And, knowing what I know about him, generations from now, there is likely to be someone else who digs into the Boyd Papers and forms a friendship with Central’s seventh president.